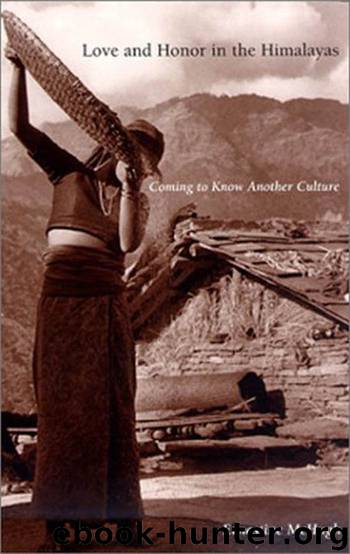

Love and Honor in the Himalayas: Coming To Know Another Culture (Contemporary Ethnography) by Ernestine McHugh

Author:Ernestine McHugh [McHugh, Ernestine]

Language: eng

Format: azw3

ISBN: 9780812202762

Publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press

Published: 2011-06-07T04:00:00+00:00

5.

Paths Without a Compass: Learning Family

Danger can enter even houses bolted against it. We went as a family to Torr, out of the village on the slippery path past the stream, through the forest that climbed up the steep slope, the trees opening to narrow waterfalls tumbling down, hewn log footbridges set across the flowing water where it met the path. After a while the forest opened onto fields. Travel was slow. We walked quickly, but each time we came to a settlement, we were called in for tea by friends or relatives. Apa would protest but they would insist (protesting and insisting are always part of social calls) and up we would go to the steps of the veranda. Bundles would be set down and we would file into the dim house, sitting in order of precedence: Apa nearest the altar, Ama after him, me next to Ama, then Seyli. Maila and Bunti had stayed behind to look after the household and the smaller children with Tson. People in the area were accustomed to me by then, so I was not the center of attention, but sat quietly by after speaking a little in Gurung and Nepali to show off Ama’s good training. The fact that I spoke, dressed, and conducted myself properly accrued to her honor and that of the family, just as my failures would diminish it. As we approached a village, she would prime me: “Now we will stop at our relatives’ house. You must call the woman ‘father’s-middle-born-sister’ (Panni). Call the man ‘husband-of-older-female-relative-on the-father’s-side’ (Aumo).” These might be distant cousins, since the terms reflected very broad categories, but the intimate and precise language created a sense of closeness. When I greeted them properly, they looked pleased. I felt happy at those moments.

Our slow progress brought us to Sohrya at evening. We called at the house of an old man and woman, who insisted that we stay. Some could sleep in the house, they said, and others in the room above the stable. The house was small but had a wide, walled courtyard, a little mill house, and a large room with a carved window above the stable. They were both erect and composed, and the woman had large, soft eyes. She was wearing a maroon brocade blouse and had a small diamond in her nose. Their son was away in the British army. “Sit,” she said to me, patting a place next to her on the mat. I was excited when they told me that many years before, in their youth, a French anthropologist had stayed with them. This must have been Bernard Pignède, a famous student of Gurung culture from Paris who was in Nepal at about that time. I had read his book. “He was agreeable,” the old man said. “He shared his food and played his tape machine for us.” I looked across the courtyard at the room he had stayed in and imagined him cooking his food there. I wondered what people would say of me in thirty years.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

Born to Run: by Christopher McDougall(7127)

The Leavers by Lisa Ko(6948)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5415)

Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harari(5370)

Spare by Prince Harry The Duke of Sussex(5197)

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(5179)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4313)

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber(4190)

Never by Ken Follett(3957)

Goodbye Paradise(3810)

Livewired by David Eagleman(3773)

Fairy Tale by Stephen King(3398)

A Dictionary of Sociology by Unknown(3085)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3073)

The Social Psychology of Inequality by Unknown(3031)

The Club by A.L. Brooks(2925)

Will by Will Smith(2919)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2845)

People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory by Dr. Brian Fagan & Nadia Durrani(2736)